This piece originally appeared on USAPP- American Politics and Policy

Are new technologies changing the way in which we conceptualise and practise politics? This is the fundamental question to which we investigate in new research. In particular, we are interested in understanding how social capital is structured in online networks. Our findings show that the traditional structures we observe in offline settings, such as traditional social movements, organisations or political parties, are replicated in the online world. Moreover, supporting others’ findings from we claim that traditional behaviour continues to play a key role in the way in which social networks are structured.

We follow the traditional approach to social capital devised by Robert Putnam, understanding it as the presence of social networks that are able to mobilise resources and information, operating under norms of trust and reciprocity. Our main claim is that the connections we make online carry the strength to create meaningful social connections. These connections, in turn, can be the trigger for further political action.

Traditionally, this idea has been contested; there is a growing group of dystopian scholars that argue that information and communication technologies are damaging the way in which we connect and interact with others. In particular, we have seen the surge of theories about social isolation, lack of community sense, and individualism. Our work takes a more sceptical approach. We believe that technology is not deterministic, and that social behaviour is a deeper trend that does not completely depend on the way in which we choose to connect with others.

Our work focuses on three different cases. We use the typology devised by Bennett and Sergeberg of what they call “connective action”: organisationally-enabled (Chilean 2013 presidential election), organisationally-brokered (UK Enough Food for Everyone ‘IF’ campaign against global hunger), and crowd-enabled (Occupy movement in the US).

We rely on Twitter data from the three cases. For the Occupy case, we have access to the Occupy Research project and their datasets. For the IF campaign, we have collected data during the main periods of the campaign. In the case of the Chilean election, we focused on the period of official campaigning, i.e. one month before the election.

Measuring social capital is always a difficult task, mainly for the different conceptual distinctions that the literature makes. In our case, we borrowed the concepts from Ronald Burt and focused on two structural elements of social capital: closure and brokerage. Closure refers to how tightly connected the members of small groups or cliques are. This relates to the notion of bridging social capital or intragroup ties. Higher levels of closure are usually related to the formation of trust among the members of the group. That is, the more you know someone and the closer you get with them, the more likely are you to trust that person.

Another important determinant of closure is homophily: people are usually attracted to interact with people who share their same interests and values. This also relates with what Putnam calls the “dark side” of social capital, the creation of very tight groups that exclude non-members. Thus, connections across these highly tight groups are essential, and that is what brokerage does. Putnam calls this bridging social capital, and is related to different political outcomes, such as political stability, trust in institutions, and social inclusion.

We calculate the network metrics for closure (clustering coefficient) and brokerage (network constraint) for each network per week. We observe the evolution of these trends over time, and analyse their relationship. In a healthy social environment, closure and brokerage should not work against the other, and that is exactly what we observe in the online cases.

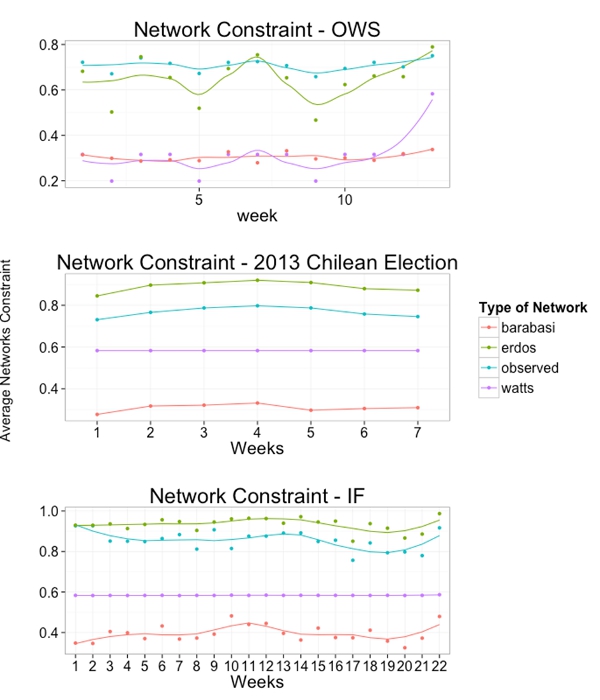

The next step was comparing these networks with different theoretical models that are aimed to explain social networks. We use the Erdos-Renyi algorithm to simulate random networks as a baseline test. Then we expand the analysis by simulating networks using the Barabasi-Albert, and the Watts-Strogatz algorithms, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 – Network constraints across campaigns

The most striking result concerns the Occupy case. According to Bennett and Sergerberg, technology can replace the role of organisations in allowing collective action to take place. Given the low transaction costs, enforcement against free riding was less relevant and, then, people could create similar forms of collective action without the need for organisations. However, our results from the Occupy case paint a different picture.

Given that Occupy is a case without the presence of formal organisations, we expected to observe this new form of social structures reflected in the networks. However, what we observe is a network with very closed small groups, but few connections among them. Conversely, in the cases where organisations do play a significant role (the IF campaign and the Chilean election), we observe higher and significant levels of bridging social capital. Figure 1 shows the levels of network constraint for each network over time. This is the metric developed by Burt, and measures how constrained a member of the network is in connecting with others. Put simply, the lower the constraint of a person, the higher the ability they have to broker social resources across the network.

In Figure 1, the observed values are compared to the theoretical simulations. In the case of the IF campaign and the Chilean election, the observed values present significantly higher levels of brokerage than the random networks (Erdos-Renyi), while the Occupy case shows lower levels of brokerage in comparison to any of the simulations. This is evidence that, at the structural level, crowd-enabled connections are not able to fulfil the same role as formal organisations.

Our research shows a new picture, perhaps more balanced, of the role of new technologies in social life. We do not believe that social media is damaging social capital, but we argue that, at least from an structural point of view, behaviour transcends the distinction between online and offline platforms.

The main limitation of our research is evident: we are not observing the content of communications across Twitter, but only their structure. This might lead to some measurement error in the way in which we approach the questions of social capital, but we also believe that the structural signatures of social capital are consequential to its content features.

This article is based on the paper ‘Tweeting Alone? An Analysis of Bridging and Bonding Social Capital in Online Networks’ in American Politics Research, co-authored with Jennifer vanHeerde-Hudson, David Hudson, Niheer Dasandi and Yannis Theocharis.