Written with Stijn van Kessel and Steven van Hauwaert. Originally published at the LSE European Politics and Policy blog

Extant research shows that supporters of populist radical left-wing and right-wing parties make conscious choices: they generally support these parties because they agree with their positions. Yet, populist party supporters are still often portrayed as ill-informed and susceptible to a charismatic leader’s evocative, yet misleading rhetoric. This is not least due to a widespread negative interpretation of “populism” as a stand-alone concept. Populism is regularly associated with political opportunism (“saying what people want to hear”), naïveté (“simple solutions to complex problems”) and demagogy (“responding to society’s underbelly”), or confused with adjacent but fundamentally different concepts, such as xenophobia or nationalism.

To what extent is this image of populist party supporters as being politically naïve or misinformed accurate? In the contemporary context of “fake news”, this question is perhaps more relevant than ever. Are populist party supporters more susceptible than their non-populist counterparts to misleading or incorrect information disseminated by politicians and (social) media? In a recently published study, we provide an initial answer to these questions.

We use a commonly accepted definition of populism, and consider it to be a set of ideas that make a moral distinction between the “corrupt elite” and the “virtuous citizens”. Accordingly, populist parties accuse the (political) elite of power abuse and, often consciously, ignoring the wishes of “ordinary” citizens. They are self-proclaimed champions of so-called “popular sovereignty”.

For our study, we rely on an existing cross-national survey with data from nine European countries (Germany, France, Greece, Italy, Poland, Spain, United Kingdom, Sweden and Switzerland) to distinguish between respondents who indicated they would, in the next elections, vote for a populist party (left or right), those who would cast a vote for a non-populist party, and those who had no intention of voting.

The main aim of our study was to investigate whether there is a connection between political support (populist choice/non-populist choice/abstaining) and political information, but also political misinformation. After all, being informed is not only a matter of possessing or lacking information; the accuracy of this information should also be considered.

With that in mind, we estimated the extent to which individuals were politically informed, uninformed or misinformed, based on three multiple choice questions that were included in the survey. Respondents were asked to recognise an EU politician, answer the question of what “budget deficit” means, and identify who sets the interest rate in their country.

Respondents who gave correct answers received a high score on a “political information” variable; those who gave incorrect answers or admitted they did not know the answers scored low, and were considered “politically uninformed”. We then also compiled an indicator for the correctness of political information, i.e. a “political misinformation” variable. Respondents who gave correct answers or admitted they did not know the answers received a low score, while respondents who gave incorrect answers received a high score, and were deemed “politically misinformed”.

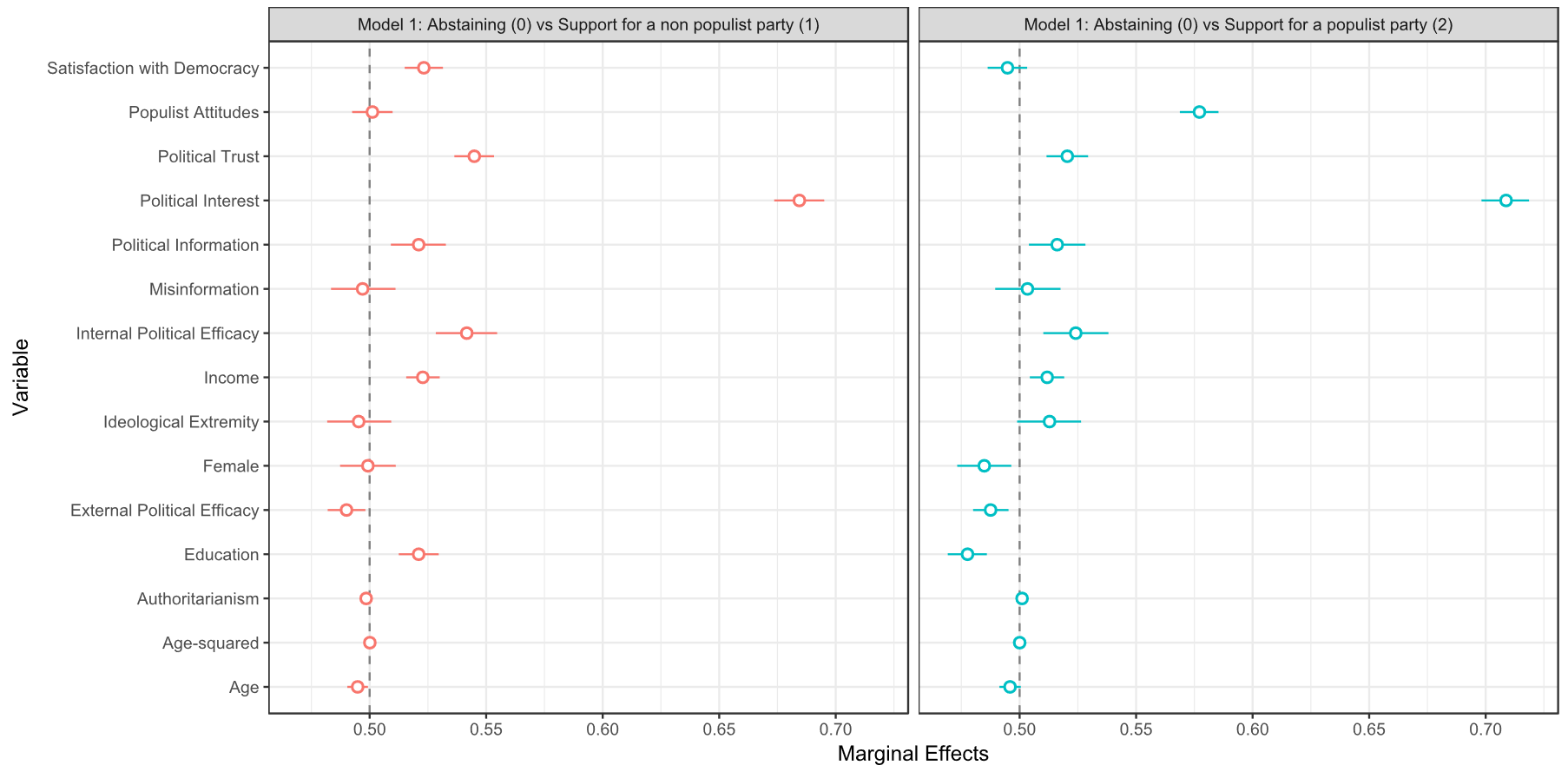

Figure 1: Multinomial logistic coefficients for the regression models (Model 1)

Note: For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in West European Politics.

What did we observe when relating the extent of (correct) information to intended voting behaviour? Model 1 shows that populist party supporters are not demonstrably worse informed than supporters of other parties. There is only a clear difference between those who intend to turn out and those who do not. On average, the latter are less informed than more politically active citizens. We thus find a positive relationship between possessing correct political information and the intention to support a political party, regardless of whether that party is populist or not.

As previous research shows, populist voters are also characterised by a high degree of political interest (compared to non-voters) and strong populist attitudes. That is, they share an aversion towards the political elite, and believe that politicians should follow “the will of the people”. These findings suggest that support for a populist party should not simply be interpreted as an uninformed “protest vote” or a sign of political ignorance. Instead, it is often a conscious expression of dissatisfaction with the functioning of representative democracy (see previous EUROPP article here), and the electorate of populist parties consists at least partly of politically aware, informed and interested citizens.

Figure 2: Logistic coefficients for regression using left- or right-wing populist parties as dependent variable (Model 2)

In terms of political _mis_information, we find a difference between supporters of populist and non-populist parties, but only when we further distinguish supporters of populist radical right parties from the rest (see Model 2). Individuals in this latter category were, on average, characterised by a higher degree of political misinformation compared with all other respondents: they had a greater tendency to give incorrect answers to political knowledge questions, instead of admitting to not knowing the answers. This seems to be in line with previous studies that link the populist radical right ideology with distorted representations of reality, such as conspiracy theories. It is safe to say that such interpretations of reality are often based on incorrect information.

What can we conclude from this last finding? The results highlight that left- and right-wing populist parties (and their voters) cannot be considered a homogeneous group. There are major ideological differences between left-wing populist parties (which mainly focus on socio-economic themes) and right-wing populist parties (which are primarily characterised by their cultural conservatism and often xenophobic views). Populism is an important common denominator, also as an “attitude” amongst various populist party supporters. However, it is clear that there are major differences between the views and general characteristics of left- and right-wing populist supporters.

Do our results indicate that populist radical right supporters are particularly susceptible to conspiracy theories and “fake news”? Unfortunately, our research does not provide a direct answer to this pertinent question. Hopefully, follow-up studies can investigate the more specific link between the deliberate dissemination of incorrect information (‘disinformation’) and voting behaviour.

This blog was first published in Dutch on the website Stuk Rood Vlees.